In October, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) suspended its strike against the U.S. Maritime Alliance (USMX) after reaching a semi-resolution. The parties punted automation with a new Jan. 15 strike deadline, and talks broke down last week. ILA President Harold Daggett still wants to roll back the current use of semi-automated cranes and gates. He insists upon “no automation” at Gulf and East Coast ports.

In response, the USMX criticized the ILA for aiming to “move our industry backward by restricting the future use of technology that has existed in some of our ports for nearly two decades.” Yikes. Sadly, the only way out of this automation dispute will be further union negotiations. However, if an employer can maintain a union-free workplace, can it ward off blue-collar workers’ trepidation over tech?

It’s a tricky issue but not insurmountable. After all, tech anxiety is a tale as old as time, and automation jitters run through every industry. Blue-collar workers’ existential worries are no different: they want assurances that their employer doesn’t want to replace them with machines.

Here are a few thoughts on how to broach the subject of automation:

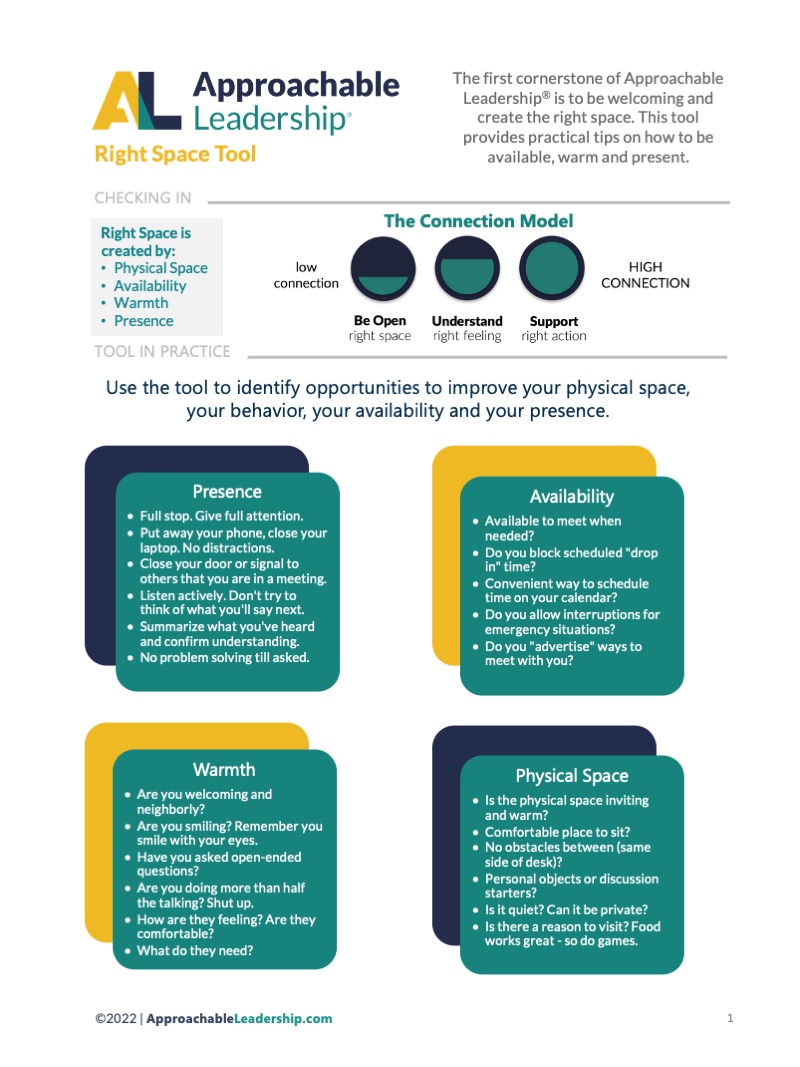

- First, a foundation of trust: Ideally, employers will have already fostered a workplace built upon open communication and kept promises so that workers will more readily embrace discussions on such a fear-stoking issue. In the words of the Brookings Institution, companies cannot count on the automation issue to “sort itself out on its own.” Letting those worries fester is a quick-serve recipe for opening the door to unions, who would be happy to fill that conversational vacuum.

- Committing to helping workers future-proof their skills on a long-term basis: Workers can sniff out BS and probably sense if an employer is only providing lip service to the subject of upskilling. Employers who regularly offer on-the-job training are more likely to be trusted with skill development related to automation, and their workers will more readily embrace working alongside new tech.

- Putting the positives into action: If workers experience how more mundane aspects of their jobs could be automated without losing job security, they’re more likely to ignore unions calling automation “a job killer.” More accurately, automation helps to ensure that the U.S. improves its own skill set. Stagnation would be the real job killer and much worse than the possibility of automation, causing the immediate loss of some jobs but creating more new ones in the process.

That final point sums up a danger posed by the ILA’s total automation ban, which would put the U.S. far behind other countries in terms of shipping capabilities and productivity. Heck, semi-automated cranes can substantially cut down loading times and instantly locate priority cargo, but the ILA doesn’t want that to happen.

It’s no wonder whether one op-ed writer wonders whether Daggett wants to “go back to taking days to load and unload ships, or workers trying to figure out how to fit random stuff on a vessel?” It seems like that might be the ILA’s real goal, to the detriment of everybody but itself.