“Wait. They’re not going back to Joy Silk?”

That was my first reaction to the Cemex decision. Nevertheless, the decision is big. But just how big? And after digging through the 150 or so pages of the opinion, what are the key takeaways? What are the unanswered questions? Here are my initial reactions.

Over the past several weeks, everyone (including me) predicted that the NLRB would return to the Joy Silk framework and usher in a new era of card-check recognition. But the Board didn’t return to Joy Silk at all.

As a quick reset, Joy Silk refers to a case adopted in 1949 and later abandoned in 1971 that required an employer to automatically recognize a union based on authorization cards (aka card check recognition). The only exception was if the company had a good faith doubt about the union’s majority status. In Cemex, the General Counsel asked the Board to return to this “good faith doubt” swamp and reinstate Joy Silk. Surprisingly, the Board declined.

This raised two immediate questions in my mind. Why did the Board’s Democrat majority decide not to return to Joy Silk as the General Counsel (not to mention the entire union movement) begged them to do? And if not Joy Silk, then what?

Let’s start with the last question. Instead of requiring employers to automatically recognize a union in most cases, the Board majority instead recognized (correctly, I might add) that employers have a statutory right to test a union’s majority status with an election by filing what’s called an RM petition. This was one of the recommendations I was making to clients when game planning how to respond to a potential Joy Silk situation. Instead, the Board majority makes that the starting point in Cemex.

The Board rules (or advises in dicta, we’ll get to that in a second) that now, when an employer is faced with a demand for recognition, it must either immediately recognize the union or “promptly” file an RM petition asking the Board to conduct an election to determine whether the union actually represents a majority.

If this were as far as the Cemex decision went, I’d be fine with it (although Member Kaplan notes that the Supreme Court in Linden Lumber already rejected this theory). Today, if a union claims majority status, the employer can refuse to recognize the union and instead tell them to file an RC petition to prove their majority status. Under Cemex, things flip, and the employer is required to recognize the union (assuming the union can prove majority status in an appropriate unit) or file an RM petition. The employer is not required to prove “good faith doubt,” and employees get a chance to vote in an NLRB-supervised secret ballot election. While the NLRB is doing its best to fast-track these elections, at least this guarantees an election in most cases. Sort of.

By deciding the case this way, the Board majority side-stepped many of the major problems with a return to Joy Silk. In most cases, the General Counsel asked the Board to make seeking an election an unfair labor practice, basically writing the employer’s right to file an RM petition out of the statute. The “good faith doubt” standard had tons of problems when it was the law of the land, and the Board was finally forced to abandon it in the face of extreme opposition from Circuit Courts of Appeal in 1971.

However, the next thing the Board majority did in Cemex was create a new bargaining order framework out of whole cloth, abandoning the Gissel doctrine laid out by the Supreme Court over 50 years ago. Under Gissel, the Board can force an employer to bargain with a union that has failed to win an election if the General Counsel can prove that:

- The union enjoyed majority support at some point (with a card majority) and

- The employer’s unfair labor practices created an atmosphere so tainted that a fair rerun election is unlikely.

What the Board majority did in Cemex will receive an even colder shoulder from Circuit Courts (and probably the Supreme Court) than a return to the “good faith doubt” swamp. I’m genuinely puzzled how the Board majority thought that gutting (or replacing) Gissel was somehow preferable to going back to Joy Silk. I don’t think either of these moves would survive review by any reviewing court. But in the words of the federal judge I clerked for, this decision is about to be kicked through the golden goalpost of life.

There are two key questions to resolve off the top.

- First, how quickly must an employer file its RM petition, and, related, when does that clock start ticking?

- Second, does a bargaining order issue for any ULP committed, only ULPs that would qualify for a bargaining order under Gissel, or something in between?

“Promptly” File

The Board majority gave a clear answer to the first question. In footnote 139 (yeah, there were a LOT of footnotes), the majority writes: “We will normally interpret “promptly” to require an employer to file its RM petition within two weeks of the union’s demand for recognition.”

This doesn’t answer when the clock starts ticking. You might say, “That’s easy; it starts when the union requests recognition.” But is it that easy? Unions often claim majority status before they file a petition or send a document asking for recognition. Because the Board is removing a requirement for the union to file an RC petition, there are a lot of games unions can play to claim they started the countdown (or, to be fair, employers can also play to say the clock didn’t start).

However, let’s assume that the Board will require some formal request to start the clock ticking, like a letter or an email. Then, the employer knows they must either recognize or file the RM petition within 14 days.

What goes on the petition? Currently, unions get to define the unit they seek to represent when they file their RC petition. But if the employer files an RM, they define the unit. That unit may not be the same as the one the union wants (this is a big part of the “good faith doubt” debate the Board side-stepped in creating its new standard). Under current unit-determination law, the union’s proposed unit is presumed appropriate, but in these cases, the union won’t have filed a petition outlining its proposed unit. I suppose if there is a disagreement, the union can file a follow-up RC petition. But this situation wasn’t discussed in the majority or dissenting opinions.

Any ULP, Gissel ULPs, or Something In-Between?

There are dueling interpretations of this between the majority and dissenting opinions. The key phrase from the majority opinion says: “… if the employer commits an unfair labor practice that requires setting aside the election, the petition (whether filed by the employer or the union) will be dismissed, and the employer will be subject to a remedial bargaining order.”

That parenthetical phrase “whether filed by the employer or the union” answers another one of my questions. It appears that this new Cemex bargaining order framework also applies when the union files an RC petition.

In footnote 142, the majority further clarifies that 8(a)(1) violations during the critical period will result in a bargaining order “unless the ‘violations . . . are so minimal or isolated that it is virtually impossible to conclude that the misconduct could have affected the election results.’”

Member Kaplan argues that the majority’s holding basically means ANY 8(a)(1) or 8(a)(3) violation during the critical period will result in a Cemex bargaining order. He writes:

“…the employer will be found to have violated Section 8(a)(5) and ordered to recognize and bargain with the union if it commits a single violation of Section 8(a)(1) or (3) after filing its petition. To warrant dismissal of the petition, the unfair labor practice must be such as would require the results of an election to be set aside, but this would amount to little more than a speed bump for the Board, if even that, given the state of Board law. The Board has recognized both that “[c]onduct violative of Section 8(a)(1) is, a fortiori, conduct which interferes with the exercise of a free and untrammeled choice in an election,” Dal-Tex Optical Co., Inc., 137 NLRB 1782,1786–1787 (1962), and that an unfair labor practice committed during the critical period requires the setting aside of an election unless it is “virtually impossible to conclude that [the violation] could have affected the results of the election,” Super Thrift Markets, Inc., 233 NLRB 409, 409 (1977).17″

Member Kaplan sees the writing on the wall. It is hard to imagine any circumstance where a ULP filed during the critical period will ever be found to be so minor as to be “virtually impossible” to affect the results of the election.

These are not Gissel orders. The Board majority goes out of its way to distinguish Cemex bargaining orders from Gissel ones, so it’s clear they aren’t the same. They even say, “the analysis of whether a bargaining order is warranted under the standard we announce today does not turn—as under Gissel—on speculation about the impact of an employer’s conduct on an election held at some future date, but rather on whether the employer has rendered a current election (normally the preferred method for ascertaining employees’ representational preferences) less reliable than a current alternative nonelection showing” (emphasis mine).

Is the Cemex framework really more efficient?

One of the arguments the majority makes is that Cemex bargaining orders will be more efficient than Gissel cases, which happen after an election and can take years to resolve. They rightly note that it’s not uncommon for Gissel bargaining orders to be denied by Circuit courts because the cases take so long to resolve that nobody remains from the original case. They like to lay the cause of this delay on the employer. But it takes two to tango (or three, if you include the union). As Member Kaplan reminds us in Cemex:

“They do not mention the fact that the General Counsel added to the delay by using this case to urge the Board to overrule five cases. More importantly, they fail to mention their own substantial contribution to delay by their decision to use this case to adopt a new (and unenforceable) standard for determining when bargaining orders should be issued, even though doing so was completely unnecessary because, as they admit, “the same . . . remedy would lie under either the prior standard [i.e., Gissel] or the standard [they] announce today.”

The other problem with this efficiency argument is that the Cemex framework still requires the Board to determine if an unfair labor practice occurred that makes a fair election unlikely. One of the major complaints courts, unions, employers, and employees have is that it takes the Board forever to resolve ULP cases. When the stakes for every ULP are now a bargaining order, this means they will be fought to the bitter end every time. This will delay elections much more than under today’s rules.

This also means the Board will have to decide how it will administratively handle what will happen in every RM case. As soon as the employer files the RM petition, rest assured that the union will file a ULP charge. At that point, the NLRB will have to decide whether to block the election (resulting in months- or sometimes years-long delay in an election) or to allow the vote to go forward. They can also choose to open the ballots pending the ULP challenge or impound them. Since unions win the vast majority of elections (begging the question of why this decision is remotely necessary), I would expect unions to ask the Board to go ahead with the election and then only pursue the ULP charge if the employer wins the election.

No matter what happens at the ballot box, because this decision requires the Supreme Court to reverse itself, these bargaining orders, once issued, will be challenged. Predictably, most employers will refuse to bargain to test the validity of the Cemex decision. Member Kaplan even makes a compelling argument that the entire section of the decision laying out the new framework is dicta, which means it is merely advisory and doesn’t even have the force of law. When employers take this route, the General Counsel will likely seek 10(j) injunctive relief, further delaying cases and increasing administrative expenses. These cases will be at least as complex and unwieldy as any Gissel case.

Can the Board create some new bargaining order outside of Gissel?

The Board majority regularly tries to distinguish these Cemex bargaining orders from the Gissel cases. At one point, they state: “Nor is there a strong justification for such a delayed attempt at determining employees’ free choice again where the Board has determined that employees had already properly designated the union as their majority representative, consistent with the language of the Act before the employer’s unfair labor practices frustrated the election process.”

But that’s exactly the situation presented in Gissel. The General Counsel is asking for a bargaining order in a situation where the union has proven it once had a card majority but no longer wants to try to prove that majority status in an election because of employer misconduct. The Supreme Court has clearly said this remedy is not favored and is only appropriate where the employer’s conduct is egregious. The Gissel Court clearly states that in many cases, “minor or less extensive unfair labor practices, which, because of their minimal impact on the election machinery, will not sustain a bargaining order.” Anything the Board does here to lighten that burden is going to get some serious scrutiny.

In Cemex, the Board makes this convoluted twist of saying that since no election ever occurred, it is somehow different from Gissel. They repeatedly state that the difference between Cemex bargaining orders and Gissel orders is that Cemex orders don’t focus on whether a future election can be fairly held. But this is a meaningless distinction. The only reason Gissel talks about future elections is because that’s the next step in those cases. But the question of whether a fair election can be held in the first place is exactly the same, and the General Counsel should have the same burden: is a fair election impossible given the employer’s unfair labor practices? If not, an election remains the gold standard for proving majority status.

Is this the end of RC petitions?

I don’t think so. This framework still incentivizes the union to file an RC petition. First, an RC eliminates the 14-day delay waiting for the employer to file its RM petition. So, a union might file to get the election process started as soon as possible. And since the majority says its bargaining order framework applies in both RC and RM situations, there is no real reason to delay.

In addition, the union may want to file to get its proposed unit definition filed first. If the employer files an RM petition, they are also defining the proposed unit. I assume the NLRB will still allow the union to name its preferred bargaining unit, but this isn’t exactly clear from the opinion. Until that’s clear, the union may choose to file the RC just to be safe.

Further, the union may not be totally confident in its majority. Often, the union guesses about the size of the bargaining unit, and often, those guesses can be wildly off. Occasionally, a union wants to start the election process even though they’re sure they don’t have a majority (this is often to get a copy of the employee list, after which they can withdraw the petition and continue getting cards signed).

As long as the union has at least 30% of the proposed unit signed up on authorization cards, they can file an RC. In the week since the Cemex decision was issued, unions are still filing RC petitions. This may just be because the opinion is brand new, or possibly there are several RMs already in the queue that just haven’t shown up. But my guess is that RCs will still be filed in many cases.

What’s Next? And what the Cemex decision didn’t do

The NLRB is about to issue an avalanche of bargaining orders. They ruled that this decision is retroactive, which means hundreds of pending election cases are about to get a Cemex bargaining order. This is going to result in a glut of appeals, a bunch of 10(j) injunction cases, and a tremendous backlog at a notoriously backlogged agency.

Nearly all these bargaining orders will get appealed. And, unlike the Cemex decision, where the Board denied the opportunity for an amicus briefing, there will be a lot of legal firepower challenging this new framework. Time will tell, but I don’t think this decision—especially step two—survives these appeals. Hopefully, courts simply say that step two is decided like any Gissel bargaining case. That would solve the most egregious problem with Cemex.

In the meantime, the majority side-stepped other important issues in Cemex. The General Counsel asked the Board to outlaw mandatory meetings related to the subject of unions. She asked the Board to apply the rule to group meetings and one-on-one conversations between a manager and an employee. While the Board declined to make this move in Cemex, this issue will be decided at some point, and the Board will likely take some action to restrict employer speech.

Further, the General Counsel asked the Board to limit employer speech under the Tri-Cast doctrine. Here, the Board is asked to restrict how an employer can refer to the change in relationship when employees become represented by a union. The General Counsel wants the Board to require employers to explain the Section 9(a) right to present grievances individually anytime they discuss the change in relationship. This is even though the exceptions to 9(a) swallow the rule (a union representative has a right to be present at these “individually” presented grievances, even if the employee doesn’t want them there, and an employer is not allowed to make any adjustment that contradicts what is in a labor agreement).

Why didn’t the Board jump at the chance to make these changes, also loudly supported by labor unions? I think there are two reasons. First, as mentioned above, the Board majority was running out of time to get this decision out before Member Wilcox’s term expired. I think that’s why they didn’t allow amicus briefing and probably why they focused this opinion on the Joy Silk issue. Second, it also makes sure that as this case winds its way up to appeal, the focus will be on one significant legal change instead of five of them. This limits the different ways an appeals court could decide the appeal.

What should employers do now?

There are several areas where employers should focus in the aftermath of Cemex.

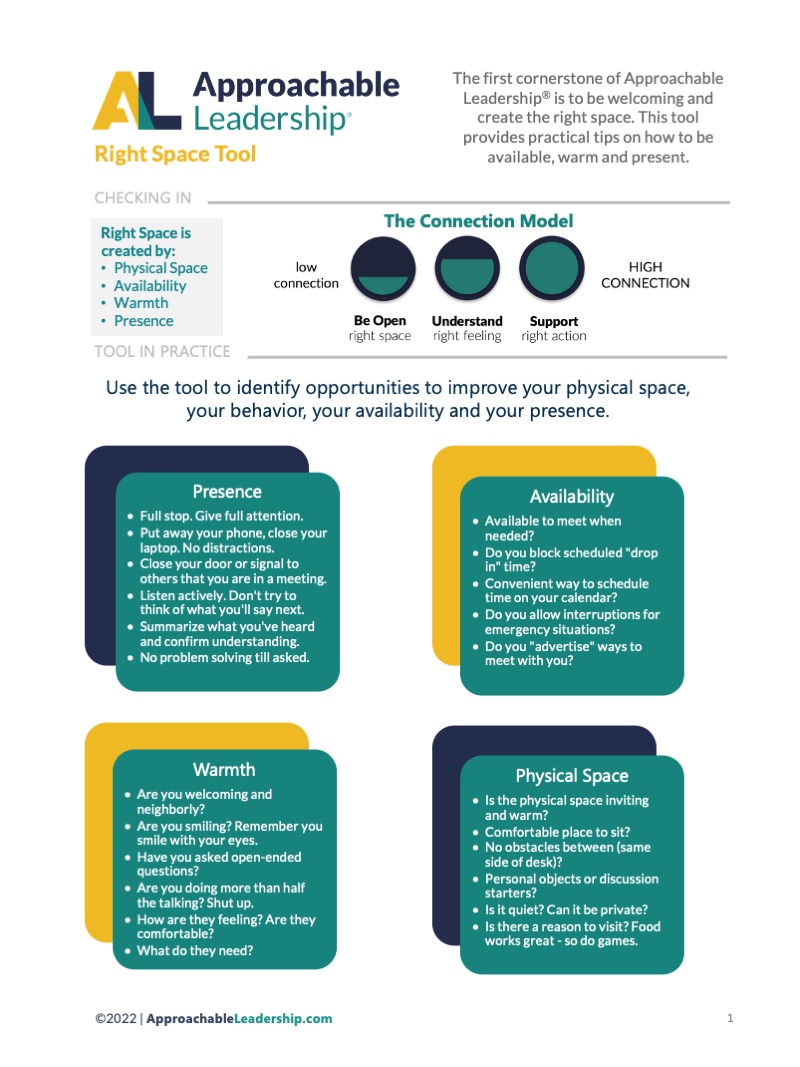

As always, the most important are Left of Boom activities. Positive employee relations practices and proactive manager training help to ensure no potential group of voters sees any benefit in representation. This ensures that a union never gains enough of a foothold among a group of workers that they can collect even 30% of the cards needed to ask for an RC election, much less the majority needed Cemex recognition. These will include:

- Positive Employee Relationships (PER) training for employees. Notice the focus on relationships. This is the keystone to every extraordinary workplace. This training emphasizes your company culture, your commitment to fair treatment and belonging, the benefits and opportunities of the employment experience, and how day-to-day problems are resolved quickly and directly. This training should be built into your hiring process, continued as part of new hire orientation, and regularly built into training for incumbent employees.

- Education on unions, including what a union is (most people have no idea or have a very distorted view from media and mythology from people with no direct experience with unions); rights and responsibilities under the National Labor Relations Act; and on the heels of Cemex, it is more important than ever to stress the value of your signature and why it is important to fully understand how unions actually work before signing an authorization card that may be the last chance you have to make a choice about unionization. Again, this should be trained early and often (although in today’s environment, you may want to make this content voluntary—seek advice from your labor counsel).

- Regular leadership training for managers, including both leader approachability content along with the union education topics listed above, plus Do’s and Don’ts training about NLRA rights and responsibilities. Post Cemex, it will be important for leaders to understand how important it is to notify top management anytime they believe a union has requested recognition. This should be regularly updated and done at least once yearly (leadership training should occur even more regularly). We have already updated our MPulse training content to include this content and ensure any messages about the direct relationship include Tri-Cast language in anticipation of that decision.

- “Always on” vulnerability assessment, which helps you direct employee relations resources where they are most needed. When it comes to employee relationships, you want to be fixing molehills before they turn into mountains. Ideally, your first-level leaders are alerting you to issues, but these relationships can be broken in at-risk workplaces. That’s why giving employees other ways to let the company know when things aren’t working how they think they should is important. These “skip-step” opportunities help you learn about potential problems before they get out of control.

- Your card-signing playbook must be updated and ready to deploy at the first signs of organizing. The whole point of Cemex, and many of the other anticipated decisions, is to severely limit the amount of time employees have to fully understand their rights under the NLRA. Union organizers (whether professionals or self-taught) will only explain a small part of the story and dramatically distort what unions can realistically promise workers. After Cemex, your employees may never get to hear the rest of the story until the union is recognized and it is too late to do anything about it. This means you must be ready to state your opinion lawfully. As the majority states in Cemex, the employer remains “fully free… consistent with Section 8(c), to express to its employees its views, arguments, or opinions on the question of representation, so long as such expressions contain no threat of reprisal or force or promise of benefit.”

- Combining Cemex with the newly announced election procedure rulemaking, which shrinks the election process by a few weeks, it is very important that you think in advance about potential bargaining units in your workplaces. You will want to be able to quickly choose a potential bargaining unit in case you have to file an RM petition with little prior notice. This means you will want to be able to prove why your proposed unit is appropriate and shares an overwhelming community of interest in case the union chooses a different unit. That takes time you won’t have after The time to think about this is now.

- This probably goes without saying, but the rapidly shrinking timeframes mean you won’t have time to figure out your team when the bullets start flying. It would be best to have your legal and consulting team identified and, ideally, working with your team on your response planning.

- Another important consideration in today’s highly public and social-media-centered campaigns is your external communication strategy. It is highly recommended to add these communications (pre-built and approved, so you don’t waste time trying to get them together when it’s too late).

These are the highlights of a response plan, but your organization will probably have needs beyond what is listed here. Now is an excellent time to tabletop your current response plan in light of these (and anticipated challenges—we are far from done).

I’m a chess player, and this Cemex decision isn’t just tilting the chess board in favor of unions. This is flipping over the Board and throwing the pieces all over the floor. It is too soon to tell how much of this new law will remain in place, but if there is any silver lining to these dramatic changes, it is this: you still hold the most crucial chess piece—your relationship with your team.

Where employee relationships are strong, your team won’t see any need to change things. More important, they won’t want to change things. And the more they look around at the scorched earth campaigns of unions over the past couple of years (with no results), the more they’ll pass on signing a union card. Now’s the time to get to work on building an extraordinary workplace.