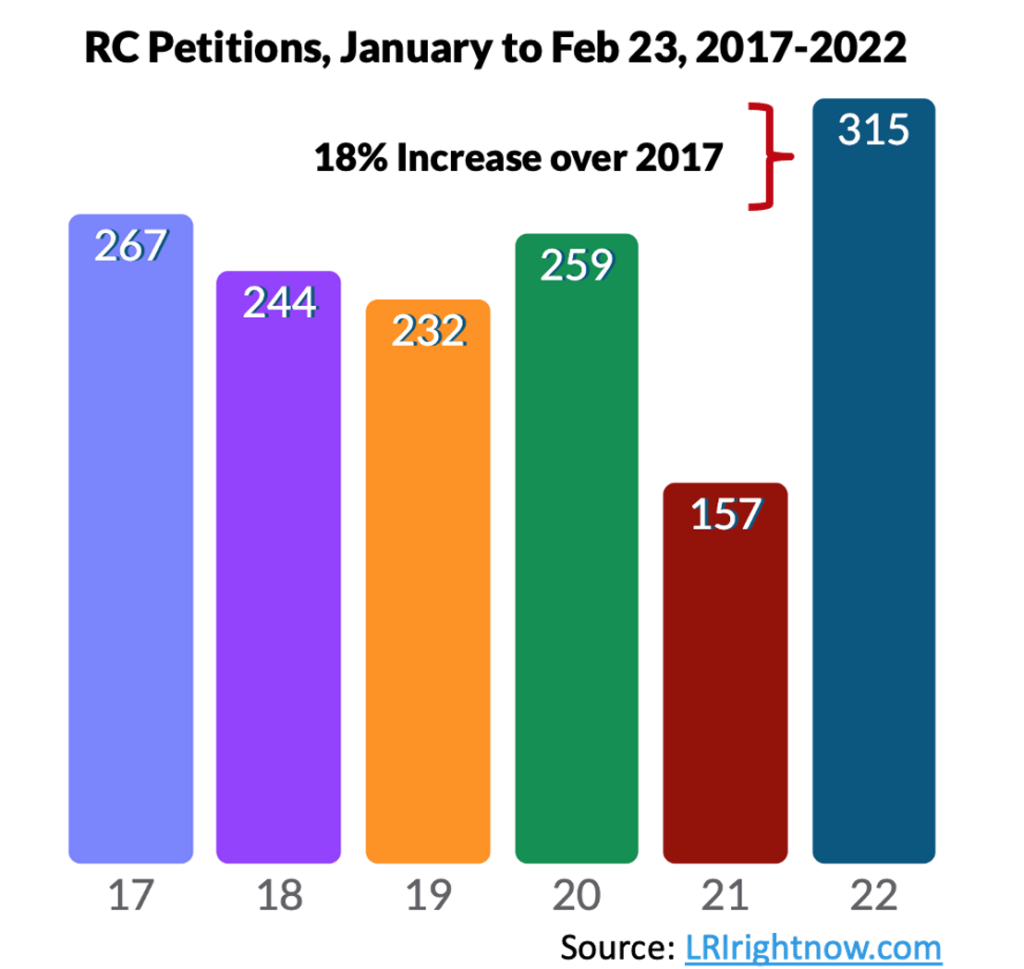

Unions are off to a blistering pace for organizing in 2022.

Late last year I predicted a record organizing year. I thought we’d break 2,000 petitions for the first time in nearly a decade. As we enter the second half of the first quarter, that prediction is looking solid. Here’s comparison of petitions for the period of January 1 to February 23 over the last 5 years:

We’re not quite through the month of February, and for the first time in the last 5 years we’ve already topped 300 petitions. In 2017 there were 1,880 petitions total. While it’s early, unions are on pace to smash that number. The record year for petitions in the last decade was 2015, when unions filed 2,169 RC petitions. During this same period in 2015 unions filed 306 petitions.

While my prediction of a record organizing year looks solid, is it correct to conclude that unions are making giant strides in organizing? Nope. With one exception unions are organizing at a slower pace in 2022 than any in the last decade except the Covid impacted 2021.

The one exception? The SEIU’s Workers United affiliate, which has filed over 100 Starbucks petitions since last August; 90 of those were filed since the beginning of the year, and 56 of those were filed this month. If you subtract the Starbucks petitions, 2022 is a disappointing organizing year so far for unions.

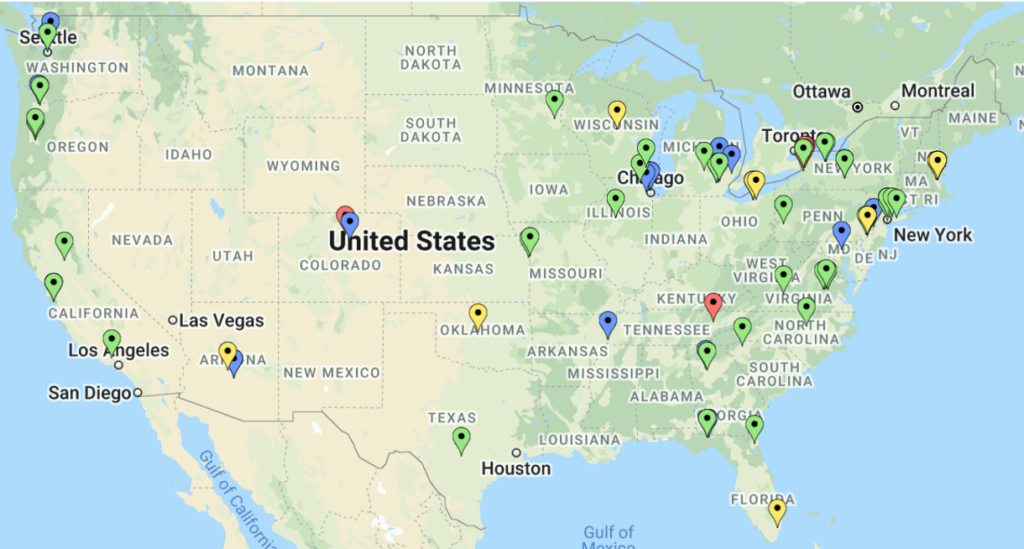

Here’s a map of the Starbucks locations impacted so far. NOTE: The green markers are petitions filed from 2/1 to 2/16.

The scale of the Starbucks campaign is unprecedented, and no matter how it ends (more on that below) it is undoubtedly one of the most successful organizing campaigns in history. While the SEIU is having its Starbucks moment, it’s worth asking two questions:

- Why are they having so much success while other unions are stuck in neutral?

- What’s the point?

Why aren’t other unions replicating what the SEIU has accomplished with Starbucks? I don’t want to discount what the SEIU has accomplished here – it should be studied in labor relations classes for years. The SEIU is probably the best organizing union there is, and the first Starbucks stores in Buffalo were a textbook case of how to organize a union, including the most important factor in any successful campaign, a highly effective “true believer” on the inside.

Jaz Brisack was the key to the initial success at the Elmwood store. Brisack is a Rhodes scholar who worked at the store for months before mentioning the union. She was trained by well-known organizing consultant (and former AFL-CIO national organizing director) Richard Bensinger, who she worked with on the Nissan campaign while in college. In addition, the campaign took advantage of the tectonic social, economic, and technological shifts that occurred under everyone’s feet during the pandemic.

At the same time, it’s hard to imagine the SEIU pulling this off during a different time or against a different company. Starbucks has a unique workforce that is almost tailor-made for a grass-roots campaign like this. And as overwhelming as this campaign must be for Starbucks, I bet if you gave truth serum to Bensinger and the SEIU they’d want the pace of these petitions to slow down (according to the Wapo article Bensinger even appears to have discouraged Brisack from taking on the coffee giant). After years of chasing trucks driving down the lane, they finally caught one that turned out to be a semi. This next phase is going to be painful for everyone.

Which brings us to the second question, what’s the point? A bunch of excited Starbucks partners are about to get a close-up view of how collective bargaining really works. Jaz Brisack is obviously quite smart, but in the Washington Post article she is quoted promising coworkers that they are guaranteed a contract that covers the cost of dues, or the SEIU would reject it. But that’s not how it works. The SEIU can ultimately accept any contract they want. And many of the other vague promises that motivated workers to sign cards are also unlikely to end up in a final labor agreement (many of them aren’t even mandatory subjects of bargaining). The reality of bargaining is a lot different than the dream world served up by organizers, the labor media, and the chattering crowds on Reddit, Discord, and TikTok.

It’s possible that is the endgame for the SEIU. They’ll use the momentum of these elections and the frustration of newly organized partners to make Starbucks the poster child of why their legislative priorities like the PRO Act should rewrite our labor laws. But an anti-corporate campaign against Starbucks seems like a stretch.

Unlike the inside of a factory or a distribution center, almost every American has been on the inside of a Starbucks. And a lot of the union rhetoric about these stores just doesn’t ring true, especially given all the things Starbucks has done to stand out as an employer of choice. An anti-corporate campaign will be painful, but it’s hard to imagine it will ultimately be effective – they almost never are.

Like a lot of these fights, the main people to benefit from this fight will be:

- The SEIU, who gets great publicity and maybe even a little dues income;

- Richard Bensinger and Jaz Brisack, who each at this point look like the next Eugene Debs (I’m sure Brisack will be hanging up her apron for a job at SEIU soon); and

- Democratic politicians who will look to mobilize these newly organized workers into political foot soldiers.

Starbucks partners at these unionized stores are the least likely to benefit because they’ve been sold a bill of goods. The end of the Wapo story tells about a five-day strike in January that Brisack and some of her coworkers engaged in over Covid protections. The store closed briefly then remained open. After five days, the workers returned with no concessions made by the store, which responded by saying it was following all CDC guidelines. Brisack is quoted saying, “How are we ever going to overthrow capitalism when it’s this hard to unionize a single store in Buffalo?” Great question.